Ocean Eyes Co., Ltd. is a technology-driven venture that leverages cutting-edge information technologies such as pattern recognition, ocean simulation, and data assimilation to develop and provide services aimed at promoting sustainable use of the oceans. Since the launch of the project that inspired our business over a decade ago, Ocean Eyes’ activities have been steadily expanding from our base in Japan to a global scale as of 2025.

In this message, we share our CEO’s thoughts and initiatives, covering the current activities of Ocean Eyes, the key principles we value, our global expansion, our service users, and the present status and future prospects of what lies at the core of our services: “the ocean and data.” CEO Yusuke Tanaka speaks broadly for those already using our services, those considering adoption, and anyone interested in themes such as “Ocean × AI,” “Ocean × Machine Learning,” or “Ocean × Data Utilization.”

Supporting the Recovery of Fisheries in the Great East Japan Earthquake Area Through the Utilization of Data

— Mr. Tanaka, CEO of Ocean Eyes, previously worked at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), where he was involved in developing ocean data assimilation systems. Could you tell us what first drew you to work in the fisheries sector?

Tanaka: I first became involved in fisheries through a project aimed at revitalizing the Sanriku offshore fishing industry, which was devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake. Many people had lost everything due to the disaster, and the project sought to leverage the power of science to rebuild fisheries more efficiently and even improve them beyond their pre-disaster state. At that time, the focus was on coastal recovery, and as an ocean researcher, I was able to contribute to the restoration of aquaculture.

We have worked to complement the traditional reliance on the experience and intuition of fishermen by providing concrete, data-driven insights—showing, for example, “This approach accelerates growth” or “This method improves quality.” By presenting these results with clear numbers, we help ensure that the people working on the ground understand and accept the recommendations, and see tangible benefits such as increased income.

Even if the fisheries themselves are restored, a decline in income can lead to fewer people working in the sector. Lower income often encourages a mindset of “catch more fish,” which can ultimately harm the industry itself and, in extreme cases, lead to overfishing. By promoting the use of data, we can contribute to fisheries from an environmental perspective, and as data analysis becomes more accurate and incomes increase, it also enhances the sustainability of the fisheries as a viable industry.

Rather than simply telling people in the fishing industry, “You should use data—it’s better,”

we believe it is essential to clearly show areas for improvement with concrete numbers and to demonstrate how these improvements ultimately translate into real income. This is exactly the kind of approach we at Ocean Eyes must continue to pursue.

The Keyword the World Is Seeking Today Is ‘Sustainability’

— Could you please introduce Ocean Eyes’ business activities and the key principles you hold dear?

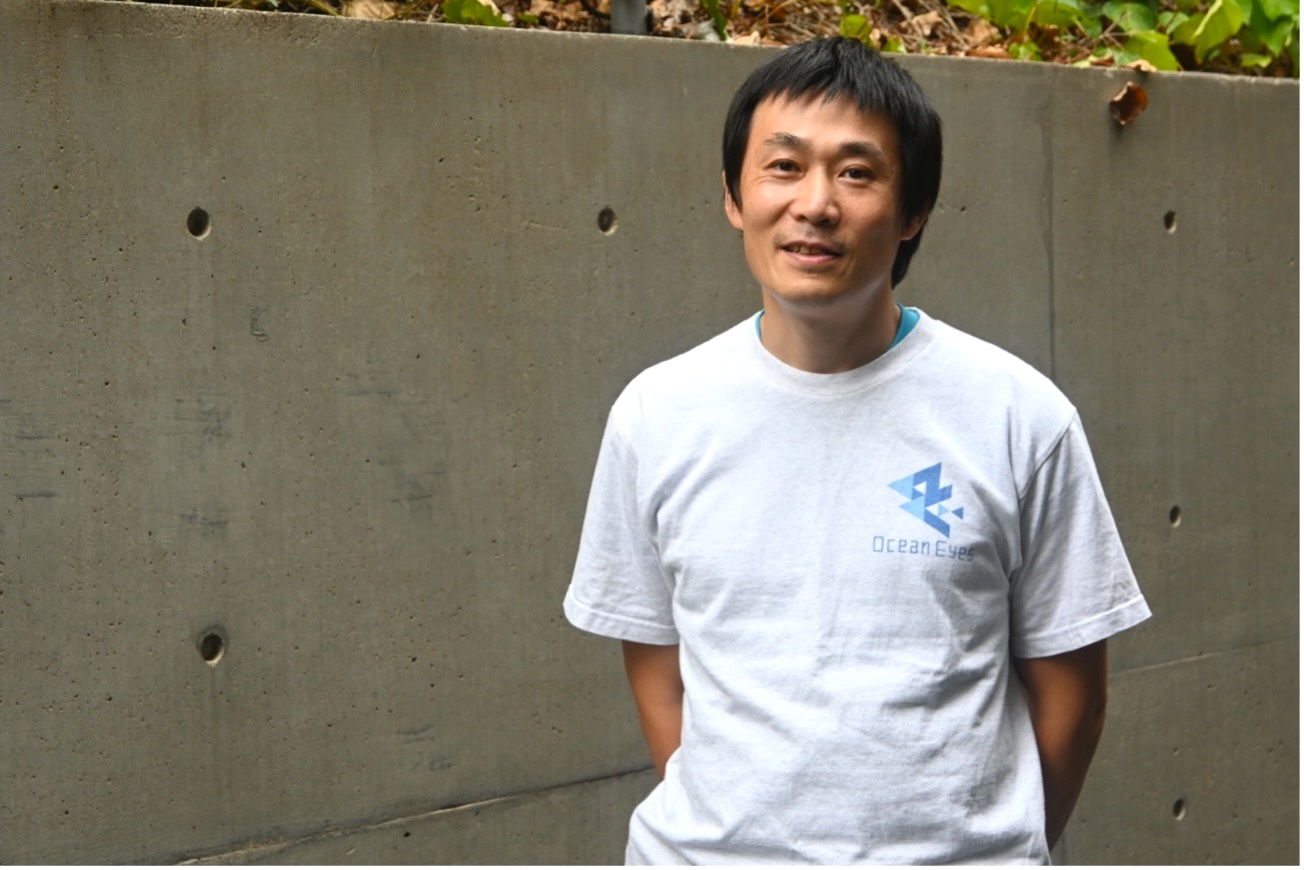

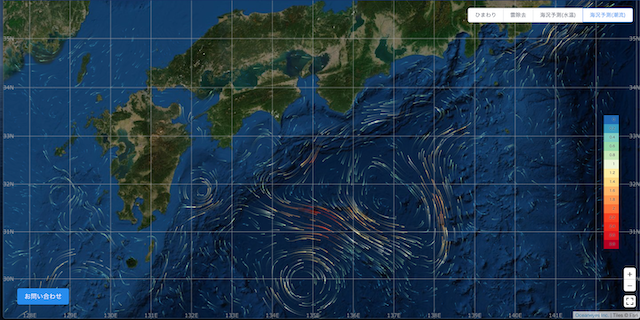

Tanaka: Ocean Eyes’ services provide “fishing ground forecasts” and “sea condition prediction” to help fishermen catch fish more efficiently and effectively.

When we give presentations at exhibitions or lectures, the first question we often get is, “Won’t this lead to overfishing?” In Japan, with both the number of fishermen and overall catch declining, some may think, “We should just catch as much as we can.” However, this perspective doesn’t always apply internationally.

Furthermore, “sustainability” has become a key concept that is in high demand and widely recognized today.

From an economic perspective for fishermen, optimizing profits within a set catch limit means that catching larger fish of the same quantity can be sold at higher prices. By using the data analysis we provide, fishermen can target larger individuals, which translates directly into increased income. From the perspective of marine resources, catching only larger, mature fish allows the next generation to grow, thereby ensuring the sustainability of the fisheries themselves.

The keyword “sustainability” comes up very frequently, especially at international exhibitions. I’ve even had students who study sustainability at university make a point of visiting the Ocean Eyes booth. I feel that this focus on sustainability is also why our services are in demand among fisheries operators.

From Japan to the World: Launching a Sea Condition Prediction App Covering Indonesian Waters

— Ocean Eyes actively showcases its services at overseas exhibitions. Could you share the current state of your international expansion?

Tanaka: In 2025, we exhibited at Europe’s largest startup and technology event, VIVA TECHNOLOGY, as well as the 10th AP2HI National Conference held in Jakarta, and we also had the opportunity to present at Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai, Japan. Additionally, a project targeting Indonesian waters was selected for JAXA’s Space Fund in 2025, and we launched a free app called OEView that allows users to access sea condition prediction data. While this is still in the PoC phase, I believe it represents a significant step forward.

Although we are currently focusing on expanding our business in Indonesia, Ocean Eyes views the entire Southeast Asian region—including Indonesia—as our broader target area. In Southeast Asia, services like fishing ground forecasting are virtually nonexistent, so our approach has been to start by providing whatever we can and putting it out there.

Tanaka: Indonesia has shown strong interest in using Ocean Eyes’ applications, driven by a sense of urgency that differs from Japan’s.

First, due to increasing catch restrictions in traditional fishing grounds in recent years, there is a growing need to rethink and modernize fishing practices. In addition, Indonesia is located in waters that are directly affected by El Niño and La Niña events. Because of these phenomena, fishing grounds can suddenly shift, making it difficult to catch fish. While we can recognize these changes by analyzing various data, people on the ground often do not have access to such information, so they find themselves in a panic, saying, “We can’t catch any fish!”

When we launched the “Fishers Navi” service in Japan, we received many comments from Japanese fishermen regarding water temperature at different depths, since the depth they want to monitor varies depending on the species they target. In contrast, in Indonesia, people currently make most of their decisions based solely on sea surface temperature. Therefore, when promoting the use of our app’s features, we plan to introduce them step by step—for example, starting with interpreting chlorophyll levels based on sea surface temperature.

The Expected Role of Ocean Eyes’ Sea Condition Prediction: Supporting the Transfer of Fishermen’s Knowledge and Skills

— What kind of people reach out to Ocean Eyes saying they want to use your services?

Tanaka: Interestingly, many of the inquiries we receive come from younger people. They tend to have a strong desire to use any tools available and to try out data if it’s accessible. And perhaps because they grew up in a world where the internet was already widespread, they feel very comfortable reaching out through a website—it’s a light, low-barrier action for them. It seems they’re willing to “just ask first” and see what’s possible.

One of the most common groups that contact us are people who have newly entered the fishing industry. Many of them have moved from outside the region to start working in fisheries (so-called “I-turn” workers) and do not have anyone nearby whom they can casually consult about fishing grounds or local practices. If they had acquaintances already working in fisheries, they could simply ask them what to do—but many do not have that network, and we receive many inquiries from people in such situations.

The transfer of fishermen’s skills is another point that has drawn attention—in fact, we were interviewed about this at an overseas exhibition. Capturing the experience and intuition of aging experts—knowledge that has traditionally been tacit, such as “this is what works”—and converting it into numerical data makes it possible to pass these skills on to the next generation. That’s a significant achievement, I believe.

We occasionally hear from experienced fishermen who are concerned about passing on their skills, though unfortunately, these inquiries are not very numerous. Nevertheless, as we continue to gather data from seasoned experts, I believe Ocean Eyes can play a meaningful role in addressing the industry-wide challenge of skill transfer to younger generations.

The Importance and Challenges of Collecting On-Site Data

— You mentioned that collecting data from experienced fishermen can be challenging. Even today, with digital devices becoming widespread, is it still difficult to gather data related to the ocean and fisheries? Does the situation vary depending on the country?

Tanaka: Even though digital devices have become widespread, the reality is that data related to the ocean is still not being adequately collected. The specific circumstances and challenges vary by country, so it’s hard to generalize, but one common issue is that usable and easily analyzable data is not being gathered. This holds true both in countries where nearly everyone has a mobile device and in countries where such devices are not yet widely available.

Officially, there are ocean data published by governments and from research projects conducted by survey vessels. At Ocean Eyes, we certainly use this information as reference data for our predictive models. However, it’s not always clear whether these datasets accurately reflect the actual conditions in a given region, and some details may be omitted when the data is released. That’s why collecting “on-site data” ourselves remains extremely important.

When we talk about “collecting data on-site,” ultimately it’s the people on the ground who gather the data. And who is actually on the ground? It’s not app developers or researchers—it’s fishermen and crew members. From their perspective, there is currently little benefit or incentive to collect ocean data, so it’s understandable that this situation exists.

There are oceanographic and research vessels, of course, but they are extremely expensive to operate—running one for a single day can cost around 10 million yen. For this reason, it’s very difficult to use research vessels casually to measure what you need.

Although it is often difficult to obtain on-site data, collecting this data is extremely important. Gathering as much data as possible and running analyses helps us better understand marine resources themselves. At Ocean Eyes, we are working on collecting fisheries-related data in collaboration with the fishing operators who currently use our services.

The Vast Public Ocean Data Collected Through International Collaboration—and Its Limitations

— The sea condition prediction service currently offered by Ocean Eyes uses publicly available data. Could you tell us more specifically about the data you use?

Tanaka: Satellite data is basically publicly available and can be used freely. In addition, autonomous ocean observation buoys—known as Argo floats—have been developed through international collaboration and are deployed across the world’s oceans. Around 3,000 buoys drift over several years, collecting measurements, and this data is published in real time.

— So does that mean much of the data is essentially “unintentionally collected,” drifting with the currents rather than being targeted?

Tanaka: Of course, if we had the budget, we could go exactly where we want and measure what we need! But the data collected within international frameworks either drifts with the ocean currents or is gathered at predetermined locations.

For example, observation buoys are equipped with CTD sensors that measure conductivity (salinity), water temperature, and depth. They are set to record temperature every meter along the depth. About once every ten days, the buoys dive from the surface down to 1,000 meters and then return to the surface, at which point the data is transmitted via satellite communication.

— With 3,000 buoys, how much of the world’s oceans are being covered?

Tanaka: You might think that “3,000 buoys worldwide” sounds like a lot, but the oceans are enormous. With this number, coverage is roughly one buoy per 300 km². Around Japan’s main islands, there are only about four buoys measuring conditions. There is also an uneven distribution—for example, the Sea of Japan has fewer buoys—and these measurements only cover the open ocean. Inland seas, such as the Seto Inland Sea, are almost completely unmonitored.

People might assume that we know a lot about waters close to urban areas, but ironically, proximity and heavy human activity make measurements difficult. Measuring water temperature in the middle of the Seto Inland Sea, for instance, is almost like trying to measure air temperature in the middle of a busy highway. The Japan Coast Guard cannot permit such dangerous operations.

Recovering Discarded Data and Putting It to Use—A Way to Change the World

— In the Seto Inland Sea, a semi-enclosed coastal sea in western Japan, many ships pass through every day, and there are frequent opportunities to board regularly scheduled vessels. If we could make use of this kind of ship data, it could open up some very interesting possibilities.

Tanaka: Whether it’s inland seas or the open ocean, I believe that if we could analyze the routes of regularly scheduled vessels, the whole picture would change dramatically.

There is data that must be provided to the Japan Coast Guard’s navigation support system, AIS, and some of it may remain onboard ships. Beyond that, ships collect a lot of data as part of their operations. I think there is significant potential to use this as analysis data.

For example, ships have intake systems for engine cooling water, and because this is engine-related, water temperature is always measured. There is also an anemometer at the top of the mast, and in the engine room, sensors exist to predict engine failures. For the operators themselves, these readings are only needed “in the moment.” Often, the numbers are not recorded at all, or if they are, they are discarded after a short period.

Simply collecting this data would make a huge difference in what we can analyze.

— When Ocean Eyes talks about the “utilization of ocean data,” this doesn’t just include fisheries—it also encompasses data held by a wide range of ocean and shipping operators. There seems to be a lot of “hidden treasure” in places where the data collectors themselves might not even recognize it as “data”.

Tanaka: If there are operators who have data but aren’t sure how to use it, we would love to hear from them. Figuring out how data can be utilized is one of Ocean Eyes’ strengths, and we can start by exploring together what can be done with the data they already have.

If records haven’t been digitized yet, the first step may simply be to start recording and digitizing them. But I think this is really where “data utilization” begins. Nowadays, there are many convenient tools available—for example, simply taking periodic photos of sensor readings and automatically converting them into text data. There are various ways to digitize without much manual effort.

What’s important, however, is to consider “utilization” in parallel with data collection.

Many projects start with “let’s attach sensors and collect data,” but often there is no discussion about what to do with the data afterward. In such cases, the value of the collected data disappears once the project ends, so the effort doesn’t continue. By planning for data utilization while collecting data, and turning previously discarded data into actionable insights, continuing to collect data becomes a clear benefit for operators.

Ideally, Ocean Eyes would pay data providers for their data, add value to it, and provide it to others—creating a circulation of value. In the long run, this could help grow the ocean data market itself, which I think would be the best outcome.

Interview Production & Editing: Nibariki, LLC

Original Japanese Text & Photography: KANO, Yoshiko